Tammero and Oyou

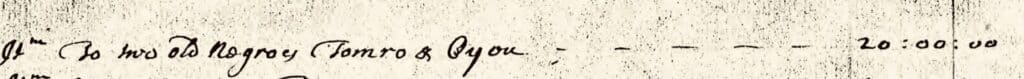

In the Last Will and Testament of Nathaniel Sylvester dated 1680, an enslaved family is listed – “Tammero (male) and Oyou (female); children, Obium (son), Tom, unnamed child, unnamed child.” Tammero and Oyou are bequeathed to Nathaniel’s 17-year-old son Peter; Obium and Tom to 23-year-old Constant; and the unnamed children to 21-year-old Benjamin. At the time of the bequests, these sons of Nathaniel and Grizzell Sylvester still resided with their mother at the Sylvester home on Shelter Island.

As with the other enslaved people of Sylvester Manor, there is no documentation about their origins; we know only some of their names. It is likely that both Tammero and Oyou were Africa born, enslaved and transported across the middle passage to Barbados. Unlike many, they retained traces of their African roots in their names.

Tammero may have been from the Igbo-speaking Ibo district of Nigeria, possibly put on a ship at the Calabar Fort headed for a Spanish port in the Americas. Africans transported on Spanish ships were routinely baptized; but if they were unsold at the first port of call, they were moved to British ports, often Barbados, and many retained names associated with their origins of embarcation or ethnicity.

Oyou’s name suggests she may have come from the Yoruba speaking kingdom of Oyo in the Western interior region of Nigeria to Barbados.

We cannot know how or when Tammero and Oyou came into Nathaniel Sylvester’s possession, what talents of theirs attracted him, or how they came together as a couple. They were among the first group of enslaved African people brought to Shelter Island from Barbados in 1652. To create the settlement at Sylvester Manor, the Africans brought there had to have the skills needed to work the land and perform the duties needed by the provisioning plantation. These skills included iron working, animal husbandry, brick making and burning charcoal, blacksmithing and working with livestock. Physical strength was needed to pack and load the vessels leaving Shelter Island for Barbados. Women needed skills in tending kitchen gardens, cooking, household chores, crafts and sewing. Life on Shelter Island for the enslaved was a hard one, full of heavy physical labor, adapting to a foreign climate and enduring the hopeless isolation and imprisonment of living in slavery on a remote, newly colonized island.

A document dated September 26, 1687 records the sale of Tammero, Oyou, Tony and Obium to James Lloyd, the husband of Nathaniel’s daughter Grizzell, for the sum of eighty-three pounds sterling to settle a debt owed by Constant Sylvester. A separate document shows the sale of Tammero’s son Tom, to James Lloyd and Sylvester cousin Isaac Arnold, for thirty pounds sterling. At this time the Lloyds lived in Boston; it is unknown if Tammero and Oyou were relocated there. It may have been the first time they had left Shelter Island since arriving thirty-six years earlier.

A year later, in September 1688, Peter Sylvester bought the couple back from Lloyd for thirty-eight pounds, and returned them to Sylvester Manor. We cannot know the reasons Peter did this, except to say that the original sale was to pay a debt and perhaps they were used as collateral until a monetary settlement could be made. At any rate, Peter Sylvester, who had inherited the couple from his father, resumed ownership of them. Tammero and Oyou may have been in their fifties or sixties by this time, older and less able to do hard work. They were brought “home” to Sylvester Manor and are more than likely among those buried in the Burying Ground on the property.

Obium

Obium, the son of Tammero and Oyou, was born in the first generation of enslaved children on Shelter Island. He was sold to James Lloyd in 1687 along with his parents, and likely sent to live in Boston when he was in his early 20s. He was likely leaving the Island for the first time in his life. When Nathaniel Sylvester died he bequeathed Obium to his son Constant, who was 23 years old in 1680. It is possible they were close in age and had grown up together on the Island.

In 1688, Peter Sylvester repurchased Obium’s parents and brought them back to Shelter Island. It was the first time the family had been separated. Soon after, Obium ran away from Boston and the Lloyds on a stolen horse. A receipt in James Lloyd’s 1693 Will notes that a reward of one pound, twenty shilling was paid for the return of “the horse Obium ran away on.” It seems likely that Obium attempted to follow his parents back to Shelter Island, despite the risks. We know that Obium, as well as the horse, were returned to Lloyd, as later documents indicate the Lloyds frequently hired him out to perform work for others. It may also have been during this period that Obium was taught to read and write.

In 1709, James Lloyd’s son Henry sent Obium to live in Newport, Rhode Island and then he was returned back to Long Island to Lloyd Manor in Oyster Bay. Henry’s father-in-law John Nelson, who Obium had been living with in Boston at the time, wrote:

“He seems to be something unwilling to part with us, but as it is a manner the same familie I tell him that upon his future good behavior he may be assured of as good treatment, he promises his best Endeavors for your Service.”

While living at Lloyd Manor, Obium married an enslaved woman named Rose, and in 1711 they had a son they named Jupiter. Rose is believed to have been born at Lloyd Manor, and, like Obium, she was taught to read and write. In an Anglican Prayer Book owned by Obium, he wrote the following inscription:

“Obium Rooe – his book. God give him Grace – 1710/11”

(the second “o” in the name may be read as an “s” indicating Obium and Rose”)

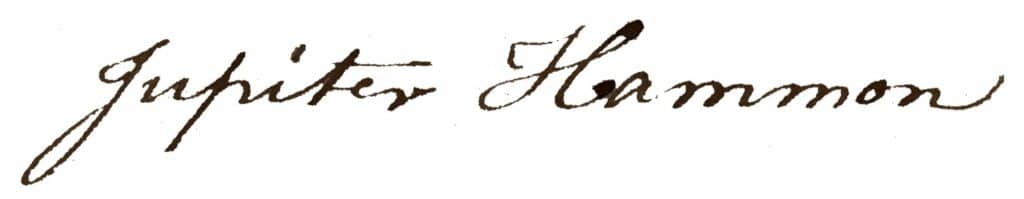

The prayer book was passed to their son, Jupiter who had taken the last name Hammon and served four generations of Lloyds. Jupiter remained enslaved all of his life but his ability to read and write enabled him to serve the Lloyds beyond physical labor and he was given a room for himself at Lloyds Manor. During this time, he became an accomplished poet with his first poem printed in 1760, making him the first African American published poet.

It is believed that Jupiter Hammon never married and the exact date of his death is unknown, though it is believed to have been before 1806.

His words and poetry live on:

A 1786 poem entitled,

“An essay on Slavery, with justification to Divine providence, that God Rules over all things,” contains the following opening lines – perhaps a reference to his own grandparents Tammero and Oyou:

Our forefathers came from Africa

Tost over the raging main

To a Christian shore there for to stay

And not return again.

Post Office Box 2029

80 North Ferry Road

Shelter Island, NY 11964 info@sylvestermanor.org 631.749.0626